Overview

Non-Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Arousal Disorders are types of parasomnias characterized by a partial arousal from a sleep state in the first third of the sleep cycle, or in what is referred to as slow wave sleep.

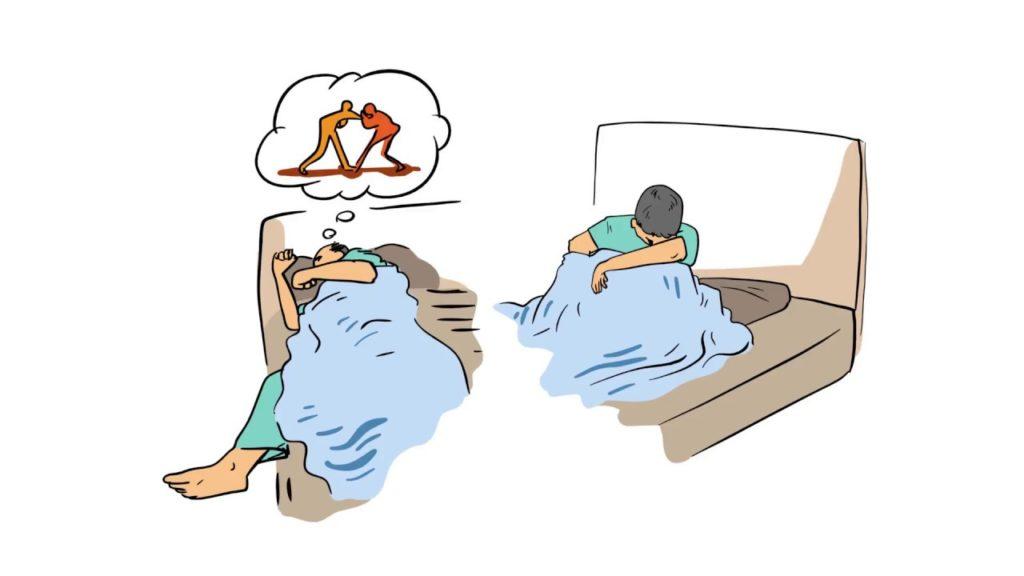

The disorders include Sleepwalking and Sleep Terrors, which can lead to significant distress, embarrassment, injury (to self or others), and impairment of interpersonal relationships.

While these disorders typically occur in childhood, they are also prevalent among adults, with further age and sex differences depending upon the type of manifestation.

Genetic, environmental, and neurological factors are considered to play a role in the aetiology of Non-Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Arousal Disorders.

Possible comorbidities, including major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder may exist.

Depending on the severity of the manifestation of symptoms, intervention may or may not be required. Environmental safety is the most important factor to be taken into consideration.

Psychotherapeutic and pharmacological means of management may be considered.

Signs and Symptoms

In case of presentation of Sleepwalking:

- Complex motor activities during sleep, including walking into closets, out of rooms and buildings, using the bathroom, talking, and so on

- Sleep-related eating

- Sleep-related sexual behavior

- Reduced alertness while sleepwalking

- Blank stare and unresponsiveness to communication while sleepwalking

- Difficulty being awakened while sleepwalking

- Inability to recall sleepwalking upon awakening

In case of presentation of Sleep Terrors:

- Sitting up suddenly in the middle of sleep

- Screaming or crying preceding and during the episode

- Evident fear during the episode

- Difficulty comforting or awakening during the episode

- Rapid breathing

- Increased heart rate

- Sweating

- Being wide-eyed

- Inability to remember most of the dream upon awakening

Risk Factors

Sex and age-related differences in the presentation of NREM (Non-Rapid Eye Movement) Sleep Arousal Disorders often depend on the type of symptomatic behavior exhibited.

Sleep-eating is more likely to occur among females, while violence or sexual activity while asleep is more common among adult males.

Sleepwalking is reportedly more prevalent among females during childhood, but males in adulthood. Sleep terrors present with a male prevalence in childhood, and equally in adulthood.

A significant genetic component is identified in the occurrence of NREM Sleep Arousal Disorders, with 80% of patients having a family history of the disorder. There is a significant chance of some form of the disorder occurring in the offspring when history of the disorder is present among both parents.

The locomotor centres are speculated to play a part in the manifestation of the disorder, with studies suggesting a disconnect between the body’s sleep state and the mind’s sleep state resulting in the complex motor behavior that is observed in NREM Sleep Arousal Disorder.

Further, the cyclic alternating pattern (CAP), which marks instability of sleep, has been associated with the disorder.

An increased rate of CAP and increased CAP cycles have been observed among individuals with sleep arousal disorders, suggesting unstable sleep as a possible risk factor.

Environmental factors are often considered as correlates. The use of sedatives or other medication, insufficient sleep, irregular sleeping schedules and disruptions in sleeping schedules, fatigue, and stress tend to increase the likelihood of NREM Sleep Arousal Disorder episodes.

Triggers such as fever, alcohol use, and the presence of other parasomnias have also been considered. States of pregnancy or menstruation may worsen the exhibition of symptoms, suggesting the possibility of hormonal correlates.

Treatment of sleep apnea through positive airway pressure has also been associated with the occurrence of the disorder.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of NREM Sleep Arousal Disorders is usually done on the basis of a thorough clinical evaluation that includes collating information given by witnesses of the exhibition of symptoms, such as parents in the case of children, or bed partners and roommates in the case of adults.

A polysomnography along with audio-visual monitoring may be carried out in order to confirm a diagnosis, or if the details of the exhibition of symptoms are unclear.

Especially in the case of paediatric presentation of the disorder, or in cases with high frequency and risk of injury to self and others, a comprehensive video-polysomnography is strongly suggested, with extended EEG and EMG montages.

The DSM-5 mentions the following diagnostic criteria for the disorder:

- Recurrent episodes of incomplete awakening from sleep, usually occurring during the first third of the major sleep episode, accompanied by either one of the following:

- Sleepwalking: Repeated episodes of rising from bed during sleep and walking about. While sleepwalking, the individual has a blank, staring face; is relatively unresponsive to the efforts of others to communicate with him or her; and can be awakened only with great difficulty.

- Sleep terrors: Recurrent episodes of abrupt terror arousals from sleep, usually beginning with a panicky scream. There is intense fear and signs of autonomic arousal, such as mydriasis, tachycardia, rapid breathing, and sweating, during each episode. There is relative unresponsiveness to efforts of others to comfort the individual during the episodes.

- No or little (e.g., only a single visual scene) dream imagery is recalled.

- Amnesia for the episodes is present.

- The episodes cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

- The disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication).

- Coexisting mental and medical disorders do not explain the episodes of sleepwalking or sleep terrors.

In case of Sleepwalking type of exhibition of symptoms, a further specification may be made in the case of sleep-eating or sleep-related sexual behavior (sexsomnia).

Treatment

The treatment of NREM Sleep Arousal Disorders is often dependent on the severity of symptoms. In cases of sleepwalking or sleep terrors in children, there is a high likelihood of the exhibition ceasing with age, and hence intervention may not be necessary.

Treating underlying disorders that may be causing symptoms, such as obstructive sleep apnea, should be prioritized. In the case of use of medication, other pharmacological alternatives may be considered.

Lifestyle factors that may trigger episodes of NREM Sleep Arousal Disorders should be taken into account and dealt with, such as insufficient sleep, stress, fatigue, and so on.

The primary step in ensuring safety in case of the manifestation of NREM Sleep Arousal Disorders is to make sure the environment around the individual is free of obstacles or potential objects that may cause harm, including furniture and sharp objects.

Windows and doors should be locked and secured. In the case of sleep terrors, anticipating the usual time of commencement and awakening the individual 15-20 minutes prior to typical occurrence has shown efficacy in stopping the episodes.

Psychotherapy for NREM Sleep Arousal Disorders may encompass behavioral therapy. In case episodes persist and are severe, pharmacotherapy may be considered.

Benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants are largely used in accordance with the type of disorder present. Clonazepam may also be used.

Differential Diagnosis

1. Nightmare disorder: In contrast to individuals with NREM sleep arousal disorders, individuals with nightmare disorder typically awaken easily and completely, report vivid dreams accompanying the episodes, and tend to have episodes later in the night.

2. Breathing-related sleep disorders: Breathing-related sleep disorders are also characterized by symptoms of snoring, breathing pauses, and daytime sleepiness. In some individuals, a breathing-related sleep disorder may lead to episodes of sleepwalking.

3. REM sleep behavior disorder: REM sleep behavior disorder may be difficult to distinguish from NREM sleep arousal disorders. REM sleep behavior disorder is characterized by episodes of prominent, complex movements, often involving personal injury from sleep. In contrast to NREM sleep arousal disorders, REM sleep behavior disorder occurs during REM sleep.

4. Parasomnia overlap syndrome: Parasomnia overlap syndrome consists of clinical and polysomnographic features of both sleepwalking and REM sleep behavior disorder.

5. Sleep-related seizures: Some types of seizures can produce episodes of unusual behaviors that occur during sleep. Nocturnal seizures may closely mimic NREM sleep arousal disorders but tend to be more stereotypic in nature, occur multiple times nightly, and are more likely to occur from daytime naps.

6. Alcohol-induced blackouts: Alcohol-induced blackouts may be associated with extremely complex behaviors in the absence of other suggestions of intoxication. They do not involve the loss of consciousness but reflect an isolated disruption of memory for events during a drinking episode.

7. Dissociative amnesia, with dissociative fugue: Dissociative fugue may be extremely difficult to distinguish from sleepwalking. Unlike all other parasomnias, nocturnal dissociative fugue arises from a period of wakefulness during sleep, rather than precipitously from sleep without intervening wakefulness

8. Malingering or other voluntary behavior occurring during wakefulness: As with dissociative fugue, malingering or other voluntary behavior occurring during wakefulness arises from wakefulness.

9. Panic disorder: Panic attacks may also cause abrupt awakenings from deep NREM sleep accompanied by fearfulness, but these episodes produce rapid and complete awakening without the confusion, amnesia, or motor activity typical of NREM sleep arousal disorders.

10. Medication-induced complex behaviors: Behaviors similar to those in NREM sleep arousal disorders can be induced by use of, or withdrawal from, substances or medications. In such cases, substance/medication-induced sleep disorder, parasomnia type, should be diagnosed.

11. Night eating syndrome: The sleep-related eating disorder form of sleepwalking is to be differentiated from night eating syndrome, in which there is a delay in the circadian rhythm of food ingestion and an association with insomnia and/or depression.

Comorbidity

In adults, there is a connection between sleepwalking and major depressive episodes and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Children or adults with sleep terrors may have higher chances of depression and anxiety on personality inventories.

Specialist

Primary healthcare providers may be involved in initial assessments of symptoms. Sleep specialists may provide accurate diagnoses and treatment.